Home Buyers May Be Better Off Sticking with Old Loan Standards

They say good things come to those who wait. But with home mortgage standards in many instances more relaxed than ever, borrowers these days don’t need to. They can get homes right away.

What We'll Cover

Some experts caution, however, that consumers might be better off holding themselves to higher credit and underwriting standards than their mortgage bankers do. With personal bankruptcy filings near their highest level ever and late payment and foreclosure rates on lenient loans either setting two-decade records or hovering just below them, they say borrowers should follow the old gambler’s adage: Bet with your head, not over it.

“The combination of the competitiveness and the political climate has really allowed us lenders to become creative in designing programs,” says Eric Burgoon, senior vice president with Old Kent Financial Corp.’s mortgage division. “You could have your rental history — in the case of a first-time home buyer — you could be late on your rent two times in the last 12 months and still qualify. You could have delinquencies on credit cards or other installment loans and, actually, you can even have a bankruptcy as long as it was three years ago, and qualify for an ‘A-‘ subprime loan.”

As for the troubling default numbers, he adds, “I think it is a concern and all prudent lenders would see that as a concern. It’s something we monitor very closely.”

The housing landscape at the end of the 20th century is, in some respects, nothing short of spectacular. Mortgage rates remain near three-decade lows. Construction of new homes and sales of existing ones have surpassed expectations for months. The homeownership rate touched a record 66.3 percent in 1998, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Public figures and industry officials are quick to praise the social stability and revenue boost that comes from a surge in home buying. But consumers who swallow too much debt in this era of easy money may live to regret it later. Ruined credit ratings, calls from collection agencies and even the loss of their piece of the American Dream can lie ahead, depending on the severity of the problem. And some troubling statistics suggest borrowers may already be headed in this direction even as the economy at large continues to chug along with a full head of steam.

| Be your own banker |

| Even if a lender doesn’t require it, a prudent borrower will: |

| Wait 12 months after the most recent delinquent payment before applying for a mortgageBuild two months worth of payments as an emergency cash reserveNot agree to a deal that consumes every available dollar of income |

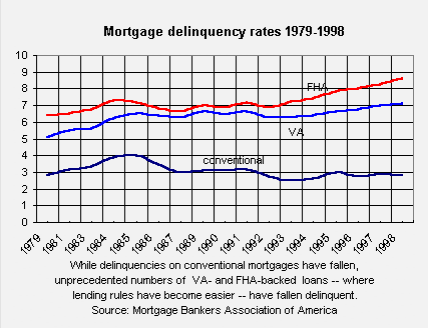

Personal bankruptcy filings soared in the 1990s, with roughly 350,000 people throwing in the towel during each of the past seven quarters, according to the American Bankruptcy Institute. On the mortgage front, the rate at which people are missing payments by 30, 60 and 90 days or more on some of the more lenient government loan programs has steadily climbed, helping to drive the U.S. foreclosure rate to a record last year.

By the end of 1998, the number of homes with delinquent mortgages stood at more than 1 million — an historic high — and more than a quarter of a million were in foreclosure, according to national statistics from the Mortgage Bankers Association of America.

Borrowers with the most lenient loans are running into the most trouble. Consider HUD’s Federal Housing Administration, or FHA, mortgage. It requires a down payment of as little as 3 percent and features looser debt-to-income qualification standards. In exchange, the customer pays an insurance premium that goes toward a government fund that covers the lender in case of default.

Marginal borrowers fall into delinquency

By the end of 1998, more than 8.5 percent of FHA borrowers were at least one month late on their mortgage payments, while almost 2.4 percent of homes were in foreclosure. These are the worst numbers since at least 1979.

The Department of Veterans Affairs, which offers loans that sometimes don’t require a down payment at all, has had trouble with its mortgages too. The delinquency rate on VA loans hit a 19-year record of 7.14 percent in the fourth quarter, according to the MBAA. The home foreclosure rate for VA loans is closing in on 2 percent, a never-before-reached level.

“You look at the most recent statistics on things like the FHA delinquency and I think the most recent numbers I saw, the delinquencies were something like eight and a half percent,” says Mike Coffey, vice president of expanding markets at Freddie Mac. “I think that’s total delinquency and that’s unheard of in the conventional market.”

That has held true to date. The delinquency rate for the tougher-to-get conventional loans, at 2.79 percent in the fourth quarter, is relatively low historically, while the foreclosure rate, at 0.71 percent, is in the middle of its two-decade range. But the so-called conventional market has undergone radical changes during the past couple years, and the full effect of today’s lenient standards won’t be known for a while.

Conventional (or conforming) loans are those which meet standards spelled out by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. The quasi-governmental agencies buy mortgages from lenders, package them together and sell them off to investors in what is known as the secondary market.

Under the guidelines of yesteryear, borrowers had to meet strict underwriting criteria to qualify for these types of loans. But today, a person with a high debt-to-income ratio, late loan payments and even a bankruptcy or foreclosure in the past can qualify for a mortgage.

Consider the following example:

Freddie Mac sends out “Seller Guide” bulletins to lenders to keep them abreast of regulatory changes. In a June 1997 note, the agency responded to the question “Why are Freddie Mac’s requirements related to bankruptcy and foreclosure so rigorous?” by writing, “Bankruptcies continue to rise and the reasons for the upward trend aren’t fully clear. And the number of repeat filers is significant. This trend, especially coupled with data that show borrowers with prior bankruptcies are more than four times as likely to go to foreclosure than borrowers with no prior bankruptcies, is alarming.”

This year, however, Freddie Mac changed its tune. The agency said that beginning May 1, certain borrowers will be able to get a loan in as few as two years after filing for bankruptcy. There’s fine print involved, and customers need to prove they’ve cleaned up their acts, but the bottom line is that financial troubles that used to knock borrowers out of the conventional marketplace for 10 years don’t necessarily do so anymore.

Why the money’s getting easier

What’s behind this development? Some cite increasing loan demand from borrowers and lenders. Others point toward competition among companies clamoring to get a piece of the mortgage market and pressure from government officials eager to promote homeownership. The lenders, for their part, say technological innovations such as their computerized underwriting systems allow them to relax guidelines without sacrificing risk management.

“There are a lot of banks that are out there that are doing below-market rates, offering closing costs assistance and doing those types of things to get these loans, No. 1, because it’s good business and No. 2, because they have to,” says Marcia Ramos, vice president and affordable lending manager for Fleet Financial Group Inc.’s mortgage company. “The demand has definitely increased and the choice the borrower has has definitely increased. They are able to shop around for the incentives when previously, those types of things weren’t available.”

Regardless of what they can qualify for, borrowers may benefit by looking at what they should qualify for instead. Doing so may just provide peace of mind, but it also might save money or even prevent a financial meltdown.

“The absolute last thing you want is a program that doesn’t properly factor in the borrower’s ability to continue to make the payment,” Coffey says. “These are people that are probably struggling because of past credit problems. They’ve stretched to come up with the necessary funds and if something should go wrong, it’s the end of their credit reputation.”

Self-protection steps for borrowers

A first step would be to evaluate whether buying a home with practically no money down is a good idea. Without the equity cushion that a 20 percent or even 10 percent down payment provides, a borrower in a depreciating housing market may find he owes more a year or two after buying than the house is worth. Low down payment loans require private mortgage insurance in many cases too, so not having money saved up will raise the cost of the monthly payment. Because of these concerns, Fleet’s Ramos recommends taking a home buying class, something many nonprofit and community groups offer.

When it comes to subprime loans, where credit history is more of a concern than amassing a down payment, every little step somebody takes can help, according to Burgoon of Old Kent.

For one, he suggests not letting a 30-day late payment turn into a 60- or 90-day delinquency because each type is progressively worse. Time also tends to heal all wounds, so waiting a little bit longer for a loan can be a wise move, especially if a late payment is nearing an anniversary. Lenders tend to look at whether a problem occurred in the last 12, 24 or even 48 months, so a consumer may be able to get a better mortgage rate by waiting until a year after a late loan payment rather than, say, 10 months.

“To the extent that they can have their credit be clean for 12 months, it will certainly help,” Burgoon says. “If they can do that for 12 straight months, that will allow you to get into at least an A-, if not a conforming, loan. That will save them a considerable amount of interest.”

Borrowers might also want to save up a couple months worth of mortgage payments to protect themselves in the event of a job loss or other problem. With many Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loans, this requirement has gone the way of the dinosaur, but adhering to it might come in handy if the economy hiccups.

As for the future, experts think consumers will likely be able to get loans with even less hassle. They say the increasing use of computerized underwriting tools and an economic environment that remains favorable will entice lenders to a larger pool of applicants.

“Clearly, as we move the (loan-to-value ratio) up and we start expanding on weaker credit, it raises the risk inherent in the loan,” says Paul Fischer, senior vice president for risk management at CMAC Investment Corp. The Philadelphia-based company underwrites the private mortgage insurance coverage that accompanies high loan-to-value, or low down payment, mortgages. “But I think the offset that everybody’s gotten comfortable with is higher pricing on those products. The expansion in the subprime market basically occurred because they were able to price up for the risk.”

Noting that lenient loan programs and computerized scoring have helped boost homeownership among minority and low-income borrowers, Fischer says the benefits of moving in that direction outweigh the drawbacks.

“It’s allowed us to expand our view of the marketplace,” he adds. “Everybody’s in the game.”

The responses below are not provided, commissioned, reviewed, approved, or otherwise endorsed by any financial entity or advertiser. It is not the advertiser’s responsibility to ensure all posts and/or questions are answered.